After visiting Lake Lalolalo we picked up Joe for the school visit. I watched as he cupped his hand under his knee to hoist himself into the car. “These damn legs are too long,” he sighed. The children were running around barefoot on the playground. Curious faces surrounded us. The school principle was wearing a flower tucked to the side of her bun greeted us with a warm smile.

I asked where I could change into my mu’umu’u for my hula lesson and was escorted into the principle’s office. This was a first. I chuckled as I bent down behind the metal desk. “Make sure you put a flower in your hair,” mom handed me one as I rolled my eyes. Twelve boys and two girls were seated. With great seriousness their teacher Eduardo with introduced Joe as a WW II veteran who served in Uvea. Joe whispered to me, “Gosh, I’m so nervous.”

"Bonjour," he began. He walked with confident determination, just slower and his hand trembled as he spoke. As he pointed to the world map, he traced the routes of armed and naval forces, blockades, battles and military strategies. His hand stopped trembling and glided over the Pacific Ocean with excitement. When his speech ended with long applause 10 year old hands shot up in the air for questions:

“Have you regret your participation in the war?”

“Was it emotional?”

“Did Wallisians participate in the war?”

“Was it difficult to forget?”

“Did you shoot anyone?”

“How did you find Uvea in those days?”

“Were you afraid?”

“Why did you sign up to fight?” asked one of the boys.

Joe turned the question to him. “If someone was attacking your country, would you fight to defend it?”

“Yes,” the boy responded. Joe smiled satisfaction and patriotism.

Joe bent down and a student presented him with a lei. Another presented a pointed wooden spear that looked at though the 5 pointed ends were singed from fire. I wondered if he had carved himself. A blond boy gifted him with a jar of preserved fruit, probably prepared by his mother. A coconut was offered to us. Coconut water tastes so refreshing when the outside temperature is 90+ ! We sipped the sweet water and ate sunset papaya. I took in the moment thinking about the preparation of picking flowers, papaya, and coconut.

For the hula lesson, the desks were pushed to the back of the classroom and we were joined by a class of younger students. To the giggles of the children, I wiggled my 'okole with much exaggeration. The boys sat in the back no doubt enjoying the sight of so many okole's doing an ami circling 'round the island.

Fosio's Recollection

Our final day in Uvea was spent visiting Fosio, whose father had befriended Joe during wartime. Fosio, 85 and his wife took care of my mom when she visited Uvea two decades after Joe. This return trip was to thank Fosio and the Taukapa family for their kindness. They embraced each other for a long time. An embrace that perhaps comes with time, wisdom, respect, and lives lost.

Our final day in Uvea was spent visiting Fosio, whose father had befriended Joe during wartime. Fosio, 85 and his wife took care of my mom when she visited Uvea two decades after Joe. This return trip was to thank Fosio and the Taukapa family for their kindness. They embraced each other for a long time. An embrace that perhaps comes with time, wisdom, respect, and lives lost.

I was asked to read the introduction to the chapter on Uvea and Joe translated into French. I was acutely aware of hearing the voice of three generations: mine, my mother’s, and Joe’s. Joe came because of his duty, mom came for self-exploration, and I came for the adventure.

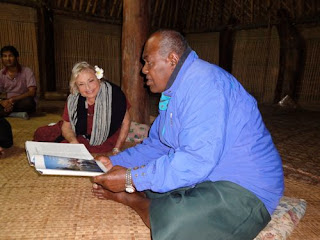

My mother had made 5x7 prints of photos that she had taken during her time in Uvea to present to the family. In one of the photos she is wearing a 60's yellow shift dress and stands in the middle of Fosio and his wife Sapolina.

With the book open, Fosio placed the photos on the page. He did not speak and looked at them over and over. His wife Sapolina had passed away a few years ago. Reverence hung in the air.

I watched Fosio and wondered what he might be thinking, perhaps traveling back in time to when the photo was taken near the stalks of banana trees. It was evident as his finger gripped the photo that he missed his wife. It was a private moment that I felt I shouldn't be watching.

As we talked and reminisced with his granddaughter and caregiver, Fosio's eyes did not leave the image. These moments you cannot describe—you feel them and they touch you. This was what we came for.

A day at the Motu

The family wanted to take us swimming at a Motu (a small atoll). It was the day before a big rugby competition and the children were let out of school early. At the end of the road was a small inlet of water. Not a harbor in the formal sense, just a place where the road met the water and we could jump in.

“Is this Lahi?” Joe asked. “This is where I first arrived in Uvea. He saluted and I took a photo.

We piled into a fishing boat. Myself, mom, Noella, the captain of the boat, and six children. Swinging one leg into the boat, I felt the excitement of my childhood.

When you grow up near the sea you search for where the horizon separates the blue of ocean and sky. You guess how deep the water is by looking at its color. The darker the blue, the deeper you are. You giggle when you see flying fish. At any moment you feel like you can jump out of the boat because you have spent years swimming, playing with the water, hopping over mini waves and riding on their crests.

Grown ups describe you like a fish in water. On field trips you go to the beach, on weekends you build castles and your friends practice burying you in sand with just your head peeking out. Things are magical. The sparkles of sunlight dance in the ripples of current. When you walk on the beach, you pick up worn sea glass, pop Portuguese man-o’war with sticks and rescue stranded bees.

I know I’ve mentioned this before but let me say it again. My mom was unconventional. During my growing up days it was mandatory to walk the dogs each morning on the beach at 5:45. We were allowed to swim at dusk under the full moon. When my sister and I would do lopsided cartwheels, even if we fell—beach walkers would clap…My childhood looked at me from the eyes of the children on the boat.

They jumped into the water once we anchored the boat off the Motu. As the men lifted mom out of the boat, I kicked off my slippers and pushed down into the white sand. Pineau, Noella’s husband was standing beneath a coconut tree fanning the flies. He came in the morning to prepare for our visit, grilling freshly caught fish, plantains, and steaming taro.

Farewell to Uvea

It was time for us to move to the next stop on our South Pacific journey. Joe planned on staying in Uvea longer. I had one of those toss and turn nights worried that we wouldn’t wake up on time for our 6 o'clock flight. Joe stumbled out of his room at 4:30 to say good bye as we stood under the stars.

“I feel like I have a new lease on life,” he thanked us. If Joe can say this at 86, you and I have a lot of learning and living.

When we arrived at the airport, the French immigration officials in their short blue navy shorts were wide awake and cheery. We were called to board and Marie Michelle and her sister Noella presented us with seed and shell leis. Tears flowed from Marie Michelle’s face, her stoicism uncloaked. I can’t pretend to know what she was thinking but I know that there was that inexplicable feeling that comes with deep love.

Welcome to my blog! Each of us has a story to tell. For my mom, well, what can I say except that she is quite the adventurer. For years her friends have asked her to write the stories that she often shares during gatherings.

Welcome to my blog! Each of us has a story to tell. For my mom, well, what can I say except that she is quite the adventurer. For years her friends have asked her to write the stories that she often shares during gatherings.