My mother could not wait. Perhaps if I were returning to a place after forty years—I might be a little anxious too. Less than 24 hours after flying into Nadi, Fiji we journeyed by four wheel drive from Sigatoka, past beaches and coconut trees leaning towards the seashore, and open Pacific blue sky. We headed for the village of Keiyasi where my mom first experienced Fiji.

We drove past villages listening to We are blessed and other spirituals selected by our driver. Mom offered to change the music to a Hawaiian CD that she’d brought. Mr. Prasad told us he’d have to stop and get out of the car and remove the CD player located under his seat which on a narrow gravel road was not a good idea.

Along for the nearly three hour journey was the grandson of the chief—a quiet, tall young man of twenty-three currently a law student at the University of the South Pacific. He didn’t say much and his eyes watched the road.

Arriving in Fiji was a fortunate accident for my mom who was on her way to someplace else. Isn’t that how it always happens? We think we know the journey that we will take and then life seems to have a different plan carrying us in a different direction, changing our route, and our life’s compass.

Arriving in Fiji was a fortunate accident for my mom who was on her way to someplace else. Isn’t that how it always happens? We think we know the journey that we will take and then life seems to have a different plan carrying us in a different direction, changing our route, and our life’s compass.At the time my mom, an aspiring photojournalist was headed for the Kingdom of Tonga on assignment with four boxers and a boxing commissioner. The wing of the plane nearly fell off and had to stop in Suva, Fiji. With a week to spare until a replacement aircraft was found, she asked for a recommendation on where should could experience real Fiji. The boxing commissioner gave her a scrap of paper scribbled with two names and a warning that it was too far into the bush to venture. Ignoring the warning, she snuck out of the hotel and boarded a bus the next morning with the name of a chief and the wife of a taxi driver. Eight hours and two buses later she arrived at the last stop, Keiyasi village, in the highlands of the island of Viti Levu. She was accompanied by a fellow passenger and a bag of roots which she was told to present to the chief for a sevu sevu ceremony.

You may be thinking what I was thinking upon journeying to Keiyasi for the first time as her daughter in this millennium. My mother was nuts. As I was about to find out---my mother’s presence was anything but forgotten. Sometimes, certain people leave an indelible human footprint on the lives of others. Such was the case with mom.

From the time we boarded the Air Pacific flight from Honolulu, I began to see how locals reacted to my mom: the fair skinned, freckled, green eyed, kai valagi woman who carries a tush cush for her arthritic back and a Japanese Tokidoki cartoon purse—just for the whimsy.

She told the flight attendant: “I am kai colo” (pronounced Thyolo). I am from the interior, from the highlands -- (the bush).” “Na yacaqu o Kalesi.” My [Fijian] name is Kalesi. The flight attendant put her hand to her mouth and started to giggle. And each time—the response would be a deep breath and an inhale with a single word: “I-----sa.” Meaning (ohhhhh). Or Io. (Yes?!).

When we arrived in Keiyasi, night was about to fall. We pulled up to a bure, a traditional building with a thatched roof made of pandanus and local grasses used as a community meeting place. We were escorted into the bure by a side entrance of steps and sat down apart from the chief facing about thirty people. Men in front. Women in back.

When we arrived in Keiyasi, night was about to fall. We pulled up to a bure, a traditional building with a thatched roof made of pandanus and local grasses used as a community meeting place. We were escorted into the bure by a side entrance of steps and sat down apart from the chief facing about thirty people. Men in front. Women in back.Peni, a man with a graying mustache that curled at either end welcomed us. His words were long and drawn out. A young man sat guarding the tanoa, a huge wooden bowl with a rope made of coconut fibers, decorated with buli, white shells at the end (usually outstretched towards the chief guest). The bowl contained yaqona (a root which had been pounded and mixed with water into a murky brown liquid which has a numbing, tranquilizing effect when consumed). Two coconut shell cups swirled the liquid in the bowl and it was poured into a polished coconut shell bowl and presented to my mother. You are supposed to clap once and then drink the bowl in one go. Then those who are welcoming you, clap in return. The coconut shell bowl was dipped in the Tanoa and poured into a separate coconut shell cup for the chief. Lastly, it was dipped for a third time and handed to me. “Is your tongue feeling numb?” My mother asked. “Yes,” I nodded. “That’s what you’re supposed to feel,” mom whispered. My cup was filled with four different welcomes. Whew!

Uraia, a friend of mom's helped her to craft a speech entirely in Fijian. Her voice began shaky and then gained momentum as she thanked the people of Keiyasi for taking care of her. She remembered the chief and the taxi driver’s wife who had passed away. She reminded everyone that Fiji held a special place in her heart. She introduced me. I can’t quite describe the feeling except that it was very humbling.

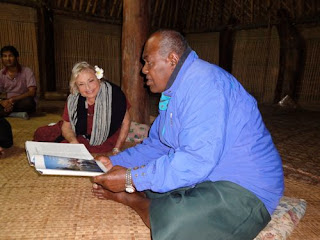

Uraia, a friend of mom's helped her to craft a speech entirely in Fijian. Her voice began shaky and then gained momentum as she thanked the people of Keiyasi for taking care of her. She remembered the chief and the taxi driver’s wife who had passed away. She reminded everyone that Fiji held a special place in her heart. She introduced me. I can’t quite describe the feeling except that it was very humbling.Sheree with Turaga-ni-koro Waisaki Nasewe (Chief of Keiyasi Village)

After the speeches of gratitude and remembrance, we moved to a small one story concrete house with a tin shed roof where we sat on the floor to a meal of fish, dalo (taro), and tomatoes. There is no electricity in Keiyasi, but we were informed that it was on its way…Perhaps in another six months as other villages a few miles down the road were wired. The interior of the house was painted a light baby blue and decorated with fabric remnants layer upon layer so that the entire room was insulated with flowers and patterns that looked like a patchwork quilt. The ceiling was lined with recycled white raffia sacks stamped with the blue and red logo of FMF--Flour Mills of Fiji. The windows looked out on the other homes in the village landscaped with red and green Ti leaves. “Once they were all thatched bures,” mom lamented. “Now they are concrete.”

While a village elder wove a mat nearby, we spent the evening talking story. Mom again and again repeated the names of everyone who befriended her and then asked about all their children. How she recalled their names was marvelous to witness. We were among progeny and younger generations and they too, felt honored. We spent time with Ani, a recent double amputee who suffered from diabetes. We discussed the possibility of a wheelchair or prosthetics to help her move around instead of having to crawl.

While a village elder wove a mat nearby, we spent the evening talking story. Mom again and again repeated the names of everyone who befriended her and then asked about all their children. How she recalled their names was marvelous to witness. We were among progeny and younger generations and they too, felt honored. We spent time with Ani, a recent double amputee who suffered from diabetes. We discussed the possibility of a wheelchair or prosthetics to help her move around instead of having to crawl.We talked about the fly problem, water situation, small health clinic staffed by one nurse, and the education of the children in the village. Life had changed but also remained the same for the people of Keiyasi. They seemed content in the day to day activities planting dalo, cassava, and sending young boys to fish from the Sigatoka river just down the hill.

Adjoining the eating area were two small rooms, each the width of a full size bed and separated from the family room by a curtain hung on a piece of string. Two women graciously gave their beds for the night so we could sleep comfortably under the mosquito net. Everyone else slept on the floor on woven mats in the same space where we ate, some of the elders using their arms as a pillow.

Levani with students at Navosa Central College in Keiyasi

What began as a peaceful evening became, well an event-filled night. Sleeping with a family of more than ten filled the evening with symphony of snoring in different octaves.

Then there were dog fights. I lay in bed staring at holes in the mosquito net wondering what they were fighting about and how many dogs were fighting (it sounded like eight). A baby began to cry and his mother hushed him to sleep over and over. The crying woke up the elders who scolded the mother to quiet the baby. My eyes were heavy and I was finally beginning to doze when the village rooster decided to sound the alarm crowing outside of my window. It’s still dark and it must be around 3:30 a.m., I thought.

Once more, I tried to let sleep envelope me but then mom needed to make a trip to the outhouse. I stumbled, grabbed my mini mag lite and escorted her past the symphony of snoring. We navigated our way around bodies, past the baby crying in the room to our left and the kitchen on our right. I unbolted the door, put on some slippers, and ventured to the outhouse in the darkness with my eyes half closed.

The next morning we asked our driver how he slept. He was invited to sleep up at the police post—where they gave him a mattress to sleep on the floor. “I didn’t sleep. The mosquitoes were singing in my ears,” he replied. I just had to laugh.

The next morning we asked our driver how he slept. He was invited to sleep up at the police post—where they gave him a mattress to sleep on the floor. “I didn’t sleep. The mosquitoes were singing in my ears,” he replied. I just had to laugh.Vasamaca weaving a mat.

Levani with our Keiyasi family

Levani, I love the stories and beautiful photos! post more when you can! love and aloha, Bec

ReplyDeleteHi Levani, Sheree,

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to your next post after following the first one. Trust you both are healthy and having a great time.

Dave and Mia