Under the mango tree

We came to an open area with a few trees one of which had been knocked over on its side, roots upturned from a recent thunderstorm. Borisi pointed. “Do you remember that is where you would rest your horse? Under that mango tree.” He started to laugh and then continued.

“I was only five then!” It never ceases to amaze me the things that stand out in our databank of memories.

It also amazes me how people find their way on unmarked roads…Using landmarks instead. You become acutely aware of your

environs and the natural shifting that occurs. Hang a left at the coconut tree. The road narrowed but was just a little wider than the old Land Rover in which we bumped along. We squeeze past two horses on the bank of the Sigatoka river and halted. Borisi disappeared past banana and coconut trees to notify someone from the village committee of our arrival. He returned with a concerned look on his face. “I think it’s too far for your mother to walk to the bure. You have to walk through the village.”

Surrounding the village was a two line barbed wire fence. After some careful negotiation and discussion one of the men returned carrying a large machete. He hacked the nail on a wooden post to which the barb wire hung. Borisi and his big bare hands, held one piece of barbed wire fence down and the other up and said “There you go, climb through.” Before ducking under the fence, my mother pulled up her mu’umu’u to reveal her impressive knee replacement scar from almost two years ago. “I have an artificial knee,” she smiled and then slowly ducked through the fence to make it through.

We took the shortcut through the village past a line of laundry, skinny dogs, and chickens. When I walk through a village, I take my time taking a panoramic photo in my mind. Once I saw a picture book where there were photographs of families and their possessions from all over the world. You could tell a person’s socioeconomic status from the photo. The house told the story of their lives.

It might just be the nature of my work, looking at life through an international development lens but looking at a family’s house, I observe who has a thatched hut or a galvanized roof and if the walls of the house are made of natural fibers or concrete—the durability of the materials used and how many and what kind of livestock if any, a family owns. Livestock and animals in village terms can serve as food but also serve as currency when trading for other goods. I look for the toilet. Most likely it is a latrine located a little afar from the house with a pit in the ground and hidden by woven leaves or covered with burlap sacks. I consider where the nearest water source is and in this case – Nuku’i’lau has the gift of being situated along the river allowing children to splash about, men and boys to fish and catch prawns, and women to bathe their children and do laundry.

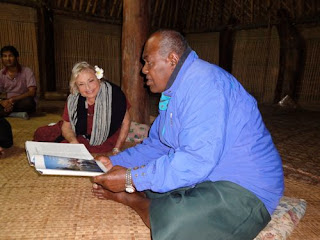

We entered the bure. Efforts were made to give my mom a chair which appeared as though it was on its last leg and a deep depression in the middle of the chair probably had seen many ‘okoles. I sat below her on the ground shooing the mosquitoes and hot air. Mom made her speech, a few Fijian phrases rolled off her tongue. She remembered her horse, Turagi-ni-koro (mayor of the village) and joked that perhaps his grandson was still alive! The serious tone cracked and there were giggles and smiles.

I looked into the faces—meeting eyes with the youth. I wondered what they wondered. How their relations and elders remember a different time, decades ago when mom was probably their age--in her 20s. I heard a echo of Appenisa, the chief’s grandson who told us in the car on the way to Keiyasi—“I’ve heard so much about you from my grandmother.” That’s the thing about when you travel—when you connect with people, you become a part of their history and they become a part of yours. They listened intently and my mom presented her book. They pointed to the picture of Keiyasi identifying relatives in the photo of the white horse standing in the Sigatoka river. When mom ended her speech with vinaka vaka levu, thank you, someone spoke up. “Aunty, tell us more stories.”

And mom began with one more story about the time that she was riding with some friends and then asked them to stay back on the trail as a joke so she could ride into a neighboring village alone---a kavalangi woman in the isolated wilderness on horseback appearing out of nowhere. Yes, mom was full of mischief and still is. Eventually, her friends joined her in the village and all was well.

Travel where you have never gone before.

Sometimes I feel like mom and I wear LCD signs on our forehead that flashes: Come with us—the Lipton ladies, we’ll take you places you have never been.

We were returning home to Keiyasi when our jeep began to skid backwards on a steep hill and our driver panicked calling out “Oh Jesus!” He then explained that he was worried that this might happen because his vehicle was not equipped for off roading, he did not bring the right tires and that if we broke down he would have to get the parts from Australia. He was used to traveling to regular tourist destinations—airport pickups, resorts drop-offs, boat trips, sightseeing, and driving along the paved Queen’s road between Nandi and Suva. We were far from all of that—deep in the interior. One way in and one way out—if you were traveling by four wheel. A horse would have been more reliable.

We were on the edge of a cliff. With a calm that betrayed my fear and concern, I said “I think we should get out of the car.” Mom, Borisi and I carefully got out of the car, while our driver gunned his engines. I held my breath considering what it would be like to overnight here. Finally the car began to move climbing each bump uphill like a turtle in slow motion eventually disappearing in a cloud of dust. It was the noontime heat of the day—the kind that makes beads of sweat fall like rain. Borisi took one hand and I took the other hand of my mom and we very very slowly climbed the hill.

The thought occurred to me for a split second, that we might just be left behind (because it almost happened to mom and I last year while on a trip to India on another road with a driver who was fumed that his van was not equipped to take us to the village where we were visiting a project for a tribal community). Once we arrived at the top of the steep hill—the jeep was there, covered in dust.

Back to School

We may not have had a choice about which road to travel to the village but we did know that education can often lead to a road of opportunity and that was our next destination. Mom and I usually make a point of asking about education as it sometimes is an indicator of a family’s economic state and a predictor of a child’s future.

We headed to Navosa Central College, the local school a short walk from Keiyasi village with this intention as we had been told that primary school was free but secondary school (equivalent to intermediate in the US) had fees. Many families could not afford tuition, books, and uniforms and hence their children dropped out.

Here’s another thing I've found when traveling, that going to school is seen as a privilege more than a routine and daily occurrence. Children know that it’s a gift to sit in a classroom expanding their minds with knowledge. They look forward to it. Most parents want their children to go to school. More often than not, it is out of necessity that they employ them to help support the family. Sometime’s I feel like kids back at home think of school as a drag and can’t wait till it’s over. We take our literacy and the power that comes with it for granted.

Here’s another thing I've found when traveling, that going to school is seen as a privilege more than a routine and daily occurrence. Children know that it’s a gift to sit in a classroom expanding their minds with knowledge. They look forward to it. Most parents want their children to go to school. More often than not, it is out of necessity that they employ them to help support the family. Sometime’s I feel like kids back at home think of school as a drag and can’t wait till it’s over. We take our literacy and the power that comes with it for granted.

Knowing this, mom decided that the best way she could say thank you to the communities of Keiyasi and Nuk’i’lau was to “invest in future generations” by providing scholarships for secondary school students. We met with the school principle, a man with a gentle face who had left his community fourteen years earlier to work here. His village was far away and he returns home to his family during holidays.

We sat in his tiny office with light green walls and windows without screens. I asked about the current situation of the school. The principle shared that at the moment the science lab was not operating because they didn’t have supplies and equipment. I thought of my friend Mahin whose biotech company has donated laboratory equipment to universities in other countries. I wondered what it would take to ship equipment from a port in New England to the port of Suva crossing the Atlantic and the Pacific united by the fact that both were former British colonies. And yet were worlds apart. I wished there was a way to get basic equipment out to this small village, things like Bunsen burners and microscopes, beakers, pipettes, catalysts and reagents. But then again when you live in a village—life around you becomes your laboratory.

I came out of my dreaming launching into reality and practical mode. The mode in which I ask questions about numbers, statistics, budgets, outcomes, and issues of transparency and accountability. School fees came to about 60-90 US dollars per student per year and slightly more for students who were boarding from Nukui'lau village which did not have a secondary school. Yes, for the price of a nice sweater and for less than the price of an iPod we could send a student to school. I live for these moments of comparative calculation.

Aloha Keiyasi

The women sat in three rows on the steps of the bure of Keiyasi. A young woman put talcum powder on our cheeks (a sign of joy) and presented each of us with a salusalu (lei) made of fragrant ixoria, frangipani, and shredded ti leaves shiny with coconut oil.

In the next moment in rich harmony and unison the women began to sing Isa Lei…sung as a friend who is departing to remind them of Fiji. It moved me and at this moment, I caught a glimpse of the tenderness and love that my mom must have felt. My heart was full but my eyes were heavy as I left my tears in Keiyasi.